Collins’ book attempts to answer the question - Why do good companies continue to be good companies? His analysis across several different industries provides meaningful insights into strong management and strategic practices.

Tech Themes

Packard’s Law. We’ve discussed Packard’s law before when analyzing the troubling acquisition history of AOL-Time Warner and Yahoo. As a reminder, Packard’s law states: “No company can consistently grow revenues faster than its ability to get enough of the right people to implement that growth and still become a great company. [And] If a company consistently grows revenue faster than its ability to get enough of the right people to implement that growth, it will not simply stagnate; it will fall.” Given Good To Great is a management focused book, I wanted to explore an example of this law manifesting itself in a recent management dilemma. Look no further than ride-sharing giant, Uber. Uber’s culture and management problems have been highly publicized. Susan Fowler’s famous blog post kicked off a series of blows that would ultimately lead to a board dispute, the departure of its CEO, and a full-on criminal investigation. Uber’s problems as a company, however, can be traced to its insistence to be the only ride-sharing service throughout the world. Uber launched several incredibly unprofitable ventures, not only a price-war with its local competitor Lyft, but also a concerted effort to get into China, India, and other locations that ultimately proved incredibly unprofitable. Uber tried to be all things transportation to every location in the world, an over-indulgence that led to the Company raising a casual $20B prior to going public. Dara Khosrowshahi, Uber’s replacement for Travis Kalanick, has concertedly sold off several business lines and shuttered other unprofitable ventures to regain financial control of this formerly money burning “logistics” pit. This unwinding has clearly benefited the business, but also limited growth, prompting the stock to drop significantly from IPO price. Dara is no stranger to facing travel challenges, he architected the spin-out of Expedia with Barry Diller, right before 9/11. Only time will tell if he can refocus the Company as it looks to run profitably. Uber pushed too far in unprofitable locations, and ran head on into Packard’s law, now having to pay the price for its brash push into unprofitable markets.

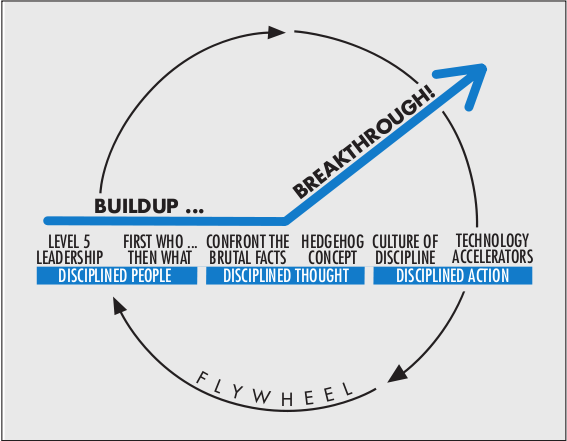

Technology Accelerators. In Collins’ Good to Great framework (pictured below), technology accelerators act as a catalyst to momentum built up from disciplined people and disciplined thought. By adapting a “Pause, think, crawl, walk, run” approach to technology, meaning a slow and thoughtful transition to new technologies, companies can establish best practices for the long-term, instead of short term gains from technology faux-feature marketing. Technology faux-feature marketing, which is decoupled from actual technology has become increasingly popular in the past few years, whereby companies adopt a marketing position that is actually complete separate from their technological sophistication. Look no further than the blockchain / crypto faux-feature marketing around 2018, when Long Island iced-tea changed its name to Long Island Blockchain, which is reminiscent of companies adding “.com” to their name in the early 2000’s. Collins makes several important distinctions about technology accelerators: technology should only be a focus if it fits into a company’s hedgehog concept, technology accelerators cannot make up for poor people choices, and technology is never a primary root cause of either greatness or decline. The first two axioms make sense, just think of how many failed, custom software projects have begun and never finished; there is literally an entire wikipedia page dedicated to exactly that. The government has also reportedly been a famous dabbler in homegrown, highly customized technology. As Collins notes, technology accelerators cannot make up for bad people choices, an aspect of venture capital that is overlooked by so many. Enron is a great example of an interesting idea turned sour by terrible leadership. Beyond the accounting scandals that are discussed frequently, the culture was utterly toxic, with employees subjected to a “Performance Review Committee” whereby they were rated on a scale of 1-5 by their peers. Employees rated a 5 were fired, which meant roughly 15% of the workforce turned over every year. The New York Times reckoned Enron is still viewed as a trailblazer for the way it combined technology and energy services, but it clearly suffered from terrible leadership that even great technology couldn’t surmount. Collins’ most controversial point is arguably that technology cannot cause greatness or decline. Some would argue that technology is the primary cause of greatness for some companies like Amazon, Apple, Google, and Microsoft. The “it was just a better search engine” argument abounds discussions of early internet search engines. I think what Collins’ is getting at is that technology is malleable and can be built several different ways. Zoom and Cloudflare are great examples of this. As we’ve discussed, Zoom started over 100 years after the idea for video calling was first conceived, and several years after Cisco had purchased Webex, which begs the question, is technology the cause of greatness for Zoom? No! Zoom’s ultimate success the elegance of its simple video chat, something which had been locked up in corporate feature complexity for years. Cloudflare presents another great example. CDN businesses had existed for years when Cloudflare launched, and Cloudflare famously embedded security within the CDN, building on a trend which Akamai tried to address via M&A. Was technology the cause of greatness for Cloudflare? No! It’s way cheaper and easier to use than Akamai. Its cost structure enabled it to compete for customers that would be unprofitable to Akamai, a classic example of a sustaining technology innovation, Clayton Christensen’s Innovator’s Dilemma. This is not to say these are not technologically sophisticated companies, Zoom’s cloud ops team has kept an amazing service running 24/7 despite a massive increase in users, and Cloudflare’s Workers technology is probably the best bet to disrupt the traditional cloud providers today. But to place technology as the sole cause for greatness would be understating the companies achievements in several other areas.

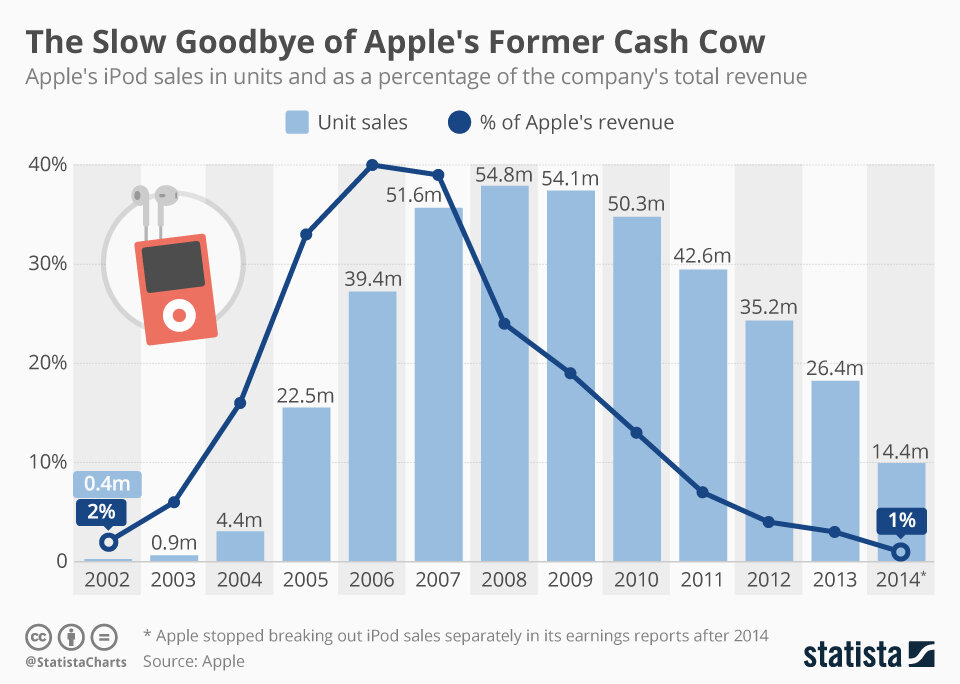

Build up, Breakthrough Flywheel. Jeff Bezos loves this book. Its listed in the continued reading section of prior TBOTM, The Everything Store. The build up, breakthrough flywheel is the culmination of disciplined people, disciplined thought and disciplined action. Collins’ points out that several great companies frequently appear like overnight successes; all of a sudden, the Company has created something great. But that’s rarely the case. Amazon is a great example of this; it had several detractors in the early days, and was dismissed as simply an online bookseller. Little did the world know that Jeff Bezos had ideas to pursue every product line and slowly launched one after the other in a concerted fashion. In addition, what is a better technology accelerator than AWS! AWS resulted from an internal problem of scaling compute fast enough to meet growing consumer demand for their online products. The company’s tech helped it scale so well that they thought, “Hey! Other companies would probably like this!” Apple is another classic example of a build-up, breakthrough flywheel. The Company had a massive success with the iPod, it was 40% of revenues in 2007. But what did it do? It cannablized itself and pursued the iPhone, with several different teams within the company pursuing it individually. Not only that, it created a terrible first version of an Apple phone with the Rokr, realizing that design was massively important to the phone’s success. The phone’s technology is taken for granted today, but at the time the touch screen was simply magical!

Business Themes

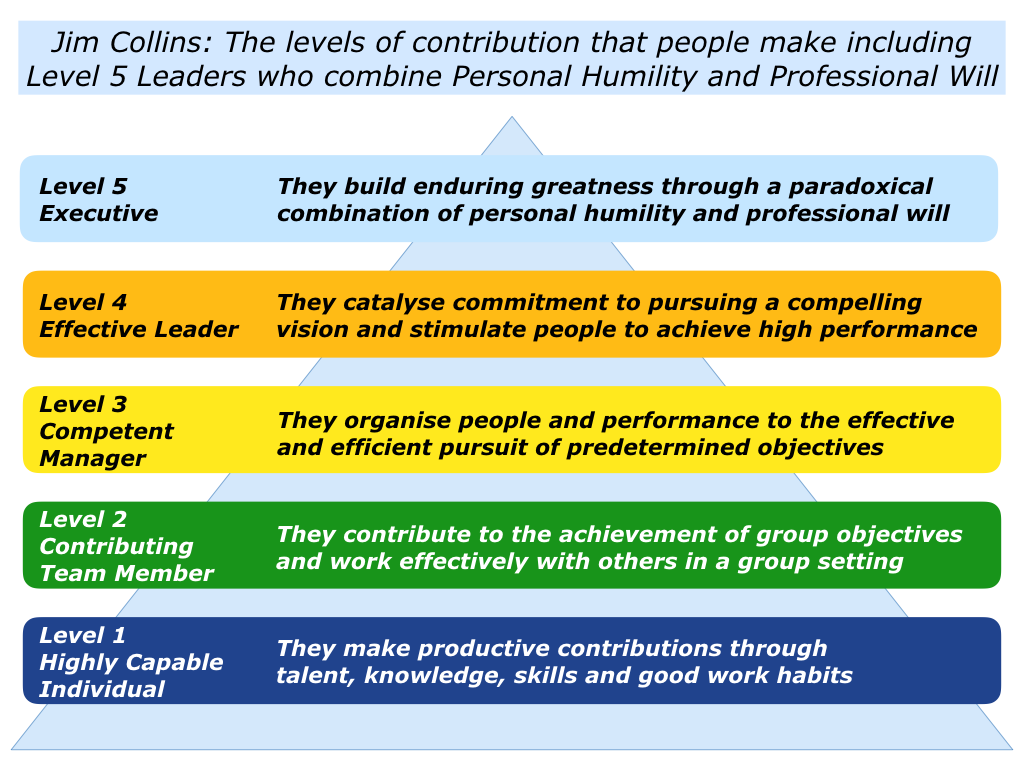

Level 5 Leader. The first part and probably the most important part of the buildup, breakthrough, flywheel is disciplined people. One aspect of Good to Great that inspired Collins’ other book Built to Last, is the idea that leadership, people, and culture determine the long-term future of a business, even after current leadership has moved on from the business. To set an organization up for long-term success, executives need to display level five leadership, which is a mix of personal humility and professional will. Collins’ leans in on Lee Iacocca as an example of a poor leader, who focused more on personal celebrity and left Chrysler to fail, when he departed. Level 5 leadership has something that you don’t frequently see in technology business leaders, humility. The technology industry seems littered with far more Larry Ellison and Elon Musk’s than any other industry, or maybe its just that tech CEOs tend to shout the loudest from their pedestals. One CEO that has done a great job of representing level five leadership is Shantanu Narayen, who took the reigns of Adobe in December 2007, right on the cusp of the financial crisis. Narayen, who’s been described as more of a doer than a talker, has dramatically changed Adobe’s revenue model, moving the business from a single sale license software business focused on lower ACV numbers, to an enterprise focused SaaS business. This march has been slow and pragmatic but the business has done incredibly well, 10xing since he took over. Adobe CFO, Mark Garrett, summarized it best in a 2015 McKinsey interview: “We instituted open dialogue with employees—here’s what we’re going through, here’s what it might look like—and we encouraged debate. Not everyone stayed, but those who did were committed to the cloud model.”

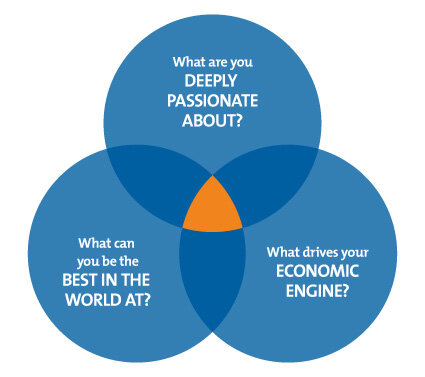

Hedgehog Concept. The Hedgehog concept (in the picture wheel to the right) is the overlap of three questions: What are you passionate about?, What are you the best in the world at?, and What drives your economic engine? This overlap is the conclusion of Collins’ memo to Confront the Brutal Facts, something that Ben Horowitz emphasizes in March’s TBOTM. Once teams have dug into their business, they should come up with a simple way to center their focus. When companies reach outside their hedgehog concept, they get hurt. The first question, about organizational passion, manifests itself in mission and value statements. The best in the world question manifests itself through value network exercises, SWOT analyses and competitive analyses. The economic engine is typically shown as a single metric to define success in the organization. As an example, let’s walk through an example with a less well-known SaaS company: Avalara. Avalara is a provider of tax compliance software for SMBs and enterprises, allowing those businesses to outsource complex and changing tax rules to software that integrates with financial management systems to provide an accurate view of corporate taxes. Avalara’s hedgehog concept is right on their website: “We live and breathe tax compliance so you don't have to.” Its simple and effective. The also list a slightly different version in their 10-K, “Avalara’s motto is ‘Tax compliance done right.’” Avalara is the best at tax compliance software, and that is their passion; they “live and breath” tax compliance software. What drives Avalara’s economic engine? They list two metrics right at the top of their SEC filings, number of core customers and net revenue retention. Core customers are customers who have been billed more than $3,000 in the last twelve months. The growth in core customers allows Avalara to understand their base of revenue. Tax compliance software is likely low churn because filing taxes is such an onerous process, and most people don’t have the expertise to do it for their corporate taxes. They will however suffer from some tax seasonality and some customers may churn and come back after the tax period has ended for a given year. Total billings allows Avalara to account for this possibility. Avalara’s core customers have grown 32% in the last twelve months, meaning its revenue should be following a similar trajectory. Net retention allows the company to understand how customer purchasing behavior changes over time and at 113% net retention, Avalara’s overall base is buying more software from Avalara than is churning, which is a positive trend for the company. What is the company the best in the world at? Tax compliance software for SMBs. Avalara views their core customer as greater than $3,000 of trailing twelve months revenue, which means they are targeting small customers. The Company’s integrations also speak to this - Shopify, Magento, NetSuite, and Stripe are all focused on SMB and mid-market customers. Notice that neither SAP nor Oracle ERP is in that list of integrations, which are the financial management software providers that target large enterprises. This means Avalara has set up its product and cost structure to ensure long-term profitability in the SMB segment; the enterprise segment is on the horizon, but today they are focused on SMBs.

Culture of Discipline. Collins describes a culture of discipline as an ability of managers to have open and honest, often confrontational conversation. The culture of discipline has to fit within a culture of freedom, allowing individuals to feel responsible for their division of the business. This culture of discipline is one of the first things to break down when a CEO leaves. Collins points on this issue with Lee Iaccoca, the former CEO of Chrysler. Lee built an intense culture of corporate favoritism, which completely unraveled after he left the business. This is also the focus of Collins’ other book, Built to Last. Companies don’t die overnight, yet it seems that way when problems begin to abound company-wide. We’ve analyzed HP’s 20 year downfall and a similar story can be shown with IBM. In 1993, IBM elected Lou Gerstner as CEO of the company. Gerstner was an outsider to technology businesses, having previously led the highly controversial RJR Nabisco, after KKR completed its buyout in 1989. He has also been credited with enacting wholesale changes to the company’s culture during his tenure. Despite the stock price increasing significantly over Gerstner’s tenure, the business lost significant market share to Microsoft, Apple and Dell. Gerstner was also the first IBM CEO to make significant income, having personally been paid hundreds of millions over his tenure. Following Gerstner, IBM elected insider Sam Palmisano to lead the Company. Sam pushed IBM into several new business lines, acquired 25 software companies, and famously sold off IBM’s PC division, which turned out to be an excellent strategic decision as PC sales and margins declined over the following ten years. Interestingly, Sam’s goal was to “leave [IBM] better than when I got there.” Sam presided over a strong run up in the stock, but yet again, severely missed the broad strategic shift toward public cloud. In 2012, Ginni Rometty was elected as new CEO. Ginni had championed IBM’s large purchase of PwC’s technology consulting business, turning IBM more into a full service organization than a technology company. Palmisano has an interesting quote in an interview with a wharton business school professor where he discusses IBM’s strategy: “The thing I learned about Lou is that other than his phenomenal analytical capability, which is almost unmatched, Lou always had the ability to put the market or the client first. So the analysis always started from the outside in. You could say that goes back to connecting with the marketplace or the customer, but the point of it was to get the company and the analysis focused on outside in, not inside out. I think when you miss these shifts, you’re inside out. If you’re outside in, you don’t miss the shifts. They’re going to hit you. Now acting on them is a different characteristic. But you can’t miss the shift if you’re outside in. If you’re inside out, it’s easy to delude yourself. So he taught me the importance of always taking the view of outside in.” Palmisano’s period of leadership introduced a myriad of organizational changes, 110+ acquisitions, and a centralization of IBM processes globally. Ginni learned from Sam that acquisitions were key toward growth, but IBM was buying into markets they didn’t fully understand, and when Ginni layered on 25 new acquisitions in her first two years, the Company had to shift from an outside-in perspective to an inside-out perspective. The way IBM had historically handled the outside-in perspective, to recognize shifts and get ahead of them, was through acquisition. But when the acquisitions occured at such a rapid pace, and in new markets, the organization got bogged down in a process of digestion. Furthermore, the centralization of processes and acquired businesses is the exact opposite of what Clayton Christensen recommends when pursuing disruptive technology. This makes it obvious why IBM was so late to the cloud game. This was a mainframe and services company, that had acquired hundreds of software businesses they didn’t really understand. Instead of building on these software platforms, they wasted years trying to put them all together into a digestible package for their customers. IBM launched their public cloud offering in June 2014, a full seven years after Microsoft, Amazon, and Google launched their services, despite providing the underlying databases and computing power for all of their enterprise customers. Gerstner established the high-pay, glamorous CEO role at IBM, which Palmisano and Ginni stepped into, with corporate jets and great expense policies. The company favored increasing revenues and profits (as a result of acquisitions) over the recognition and focus on a strategic market shift, which led to a downfall in the stock price and a declining mindshare in enterprises. Collins’ understands the importance of long term cultural leadership. “Does Palmisano think he could have done anything differently to set IBM up for success once he left? Not really. What has happened since falls to a new coach, a new team, he says.”