This month we go back to tech giant Amazon and review all of Jeff Bezos’s letters to shareholders. This book describes Amazon’s journey from e-commerce to cloud to everything in a quick and fascinating read!

Tech Themes

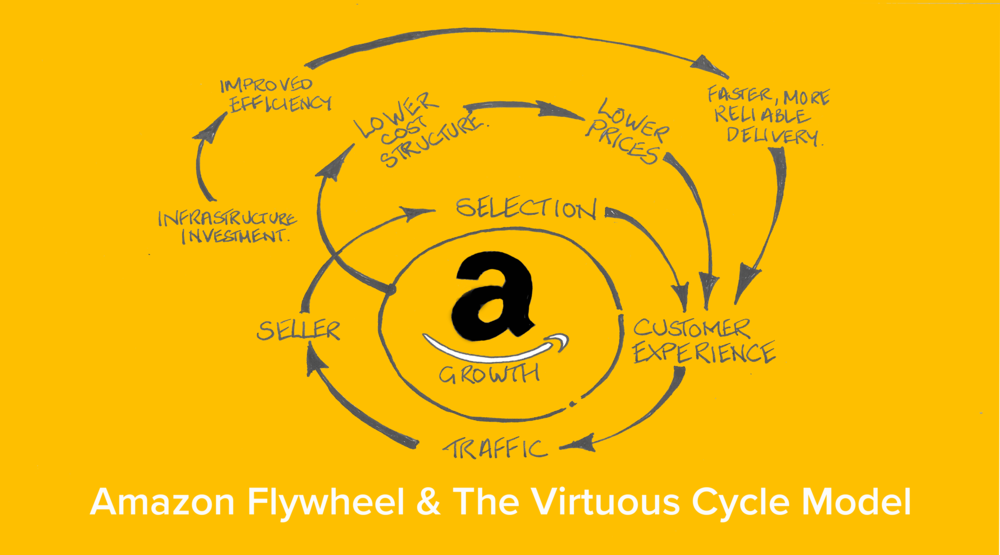

The Customer Focus. These shareholder letters clearly show that Amazon fell in love with its customer and then sought to hammer out traditional operational challenges like cycle times, fulfillment times, and distribution capacity. In the 2008 letter, Bezos calls out: "We have strong conviction that customers value low prices, vast selection, and fast, convenient delivery and that these needs will remain stable over time. It is difficult for us to imagine that ten years from now, customers will want higher prices, less selection, or slower delivery." When a business is so clearly focused on delivering the best customer experience, with completely obvious drivers, its no wonder they succeeded. The entirety of the 2003 letter, entitled "What's good for customers is good for shareholders" is devoted to this idea. The customer is "divinely discontented" and will be very loyal until there is a slightly better service. If you continue to offer lower prices on items, more selection of things to buy, and faster delivery - customers will continue to be happy. Those tenants are not static - you can continually lower prices, add more items, and build more fulfillment centers (while getting faster) to keep customers happy. This learning curve continues in your favor - higher volumes mean cheaper to buy, lower prices means more customers, more items mean more new customers, higher volumes and more selection force the service operations to adjust to ship more. The flywheel continues all for the customer!

Power of Invention. Throughout the shareholder letters, Bezos refers to the power of invention. From the 2018 letter: "We wanted to create a culture of builders - people who are curious, explorers. They like to invent. Even when they're experts, they are "fresh" with a beginner's mind. They see the way we do things as just the way we do things now. A builder's mentality helps us approach big, hard-to-solve opportunities with a humble conviction that success can come through iteration: invent, launch, reinvent, relaunch, start over, rinse, repeat, again and again." Bezos sees invention as the ruthless process of trying and failing repeatedly. The importance of invention was also highlighted in our January book 7 Powers, with Hamilton Helmer calling the idea critical to building more and future S curves. Invention is preceded by wandering and taking big bets - the hunch and the boldness. Bezos understands that the stakes for invention have to grow, too: "As a company grows, everything needs to scale, including the size of your failed experiments. If the size of your failures isn't growing, you're not going to be inventing at a size that can actually move the needle." Once you make these decisions, you have to be ready to watch the business scale, which sounds easy but requires constant attention to customer demand and value. Amazon's penchant for bold bets may inform Andy Jassy's recent decision to spend $10B making a competitor to Elon Musk/SpaceX's Starlink internet service. This decision is a big, bold bet on the future - we'll see if he is right in time.

Long-Term Focus. Bezos always preached trading off the short-term gain for the long-term relationship. This mindset shows up everywhere at Amazon - selling an item below cost to drive more volumes and give consumers better prices, allowing negative reviews on sites when it means that Amazon may sell fewer products, and providing Prime with ever-faster and free delivery shipments. The list goes on and on - all aspects focused on building a long-term moat and relationship with the customer. However it's important to note that not every decision pans out, and it's critical to recognize when things are going sideways; sometimes, you get an unmistakable punch in the mouth to figure that out. Bezos's 2000 shareholder letter started with, "Ouch. It's been a brutal year for many in the capital markets and certainly for Amazon.com shareholders. As of this writing, our shares are down more than 80 percent from when I wrote you last year." It then went on to highlight something that I didn't see in any other shareholder letter, a mistake: "In retrospect, we significantly underestimated how much time would be available to enter these categories and underestimated how difficult it would be for a single category e-commerce companies to achieve the scale necessary to succeed…With a long enough financing runway, pets.com and living.com may have been able to acquire enough customers to achieve the needed scale. But when the capital markets closed the door on financing internet companies, these companies simply had no choice but to close their doors. As painful as that was, the alternative - investing more of our own capital in these companies to keep them afloat- would have been an even bigger mistake." During the mid to late 90s, Amazon was on an M&A and investment tear, and it wasn't until the bubble crashed that they looked back and realized their mistake. Still, optimizing for the long term means admitting those mistakes and changing Amazon's behavior to improve the business. When thinking long-term, the company continued to operate amazingly well.

Business Themes

Free Cash Flow per Share. Despite historical rhetoric that Bezos forewent profits in favor of growth, his annual shareholder letters continually reinforce the value of upfront cash flows to Amazon's business model. If Amazon could receive cash upfront and manage its working capital cycle (days in inventory + days AR - days AP), it could scale its operations without requiring tons of cash. He valued the free cash flow per share metric so intensely that he spent an entire shareholder letter (2004) walking through an example of how earnings can differ from cash flow in businesses that invest in infrastructure. This maniacal focus on a financial metric is an excellent reminder that Bezos was a hedge fund portfolio manager before starting Amazon. These multiple personas: the hedge fund manager, the operator, the inventor, the engineer - all make Bezos a different type of character and CEO. He clearly understood financials and modeling, something that can seem notoriously absent from public technology CEOs today.

A 1,000 run home-run. Odds and sports have always captivated Warren Buffett, and he frequently liked to use Ted Williams's approach to hitting as a metaphor for investing. Bezos elaborates on this idea in his 2014 Letter (3 Big Ideas): "We all know that if you swing for the fences, you're going to strike out a lot, but you're also going to hit some home runs. The difference between baseball and business, however, is that baseball has a truncated outcome distribution. When you swing, no matter how well you connect with the ball, the most runs you can get is four. In business, every once in a while, when you step up to the plate, you can score one thousand runs. This long-tailed distribution of returns is why its important to be bold. Big winners pay for so many experiments." AWS is certainly a case of a 1,000 run home-run. The company incubated the business and first wrote about it in 2006 when they had 240,000 registered developers. By 2015, AWS had 1,000,000 customers, and is now at a $74B+ run-rate. This idea also calls to mind Monish Pabrai's Spawners idea - or the idea that great companies can spawn entirely new massive drivers for their business - Google with Waymo, Amazon with AWS, Apple with the iPhone. These new businesses require a lot of care and experimentation to get right, but they are 1,000 home runs, and taking bold bets is important to realizing them.

High Standards. How does Amazon achieve all that it does? While its culture has been called into question a few times, it's clear that Amazon has high expectations for its employees. The 2017 letter addresses this idea, diving into whether high standards are intrinsic/teachable and universal/domain-specific. Bezos believes that standards are teachable and driven by the environment while high standards tend to be domain-specific - high standards in one area do not mean you have high standards in another. This discussion of standards also calls back to Amazon's 2012 letter entitled "Internally Driven," where Bezos argues that he wants proactive employees. To identify and build a high standards culture, you need to recognize what high standards look like; then, you must have realistic expectations for how hard it should be or how long it will take. He illustrates this with a simple vignette on perfect handstands: "She decided to start her journey by taking a handstand workshop at her yoga studio. She then practiced for a while but wasn't getting the results she wanted. So, she hired a handstand coach. Yes, I know what you're thinking, but evidently this is an actual thing that exists. In the very first lesson, the coach gave her some wonderful advice. 'Most people,' he said, 'think that if they work hard, they should be able to master a handstand in about two weeks. The reality is that it takes about six months of daily practice. If you think you should be able to do it in two weeks, you're just going to end up quitting.' Unrealistic beliefs on scope – often hidden and undiscussed – kill high standards." Companies can develop high standards with clear scope and corresponding challenge recognition.