This month we check out Satya Nadella’s favorite book - Mindset, by Carol Dweck. The book has become an international sensation and we find out why!

Tech Themes

Growth vs. Fixed Mindset. The book’s main argument is about the distinction between a growth mindset vs. a fixed mindset. A fixed mindset supposes that one’s abilities are fixed in nature - “I am smart because my parents were smart,” “I am good at sports without trying,” “I am good at tests because I just am.” People with fixed mindsets, who believe that people’s abilities largely can’t change, find themselves frequently feeling scared to make mistakes or be wrong. In contrast, a growth mindset supposes that people can drastically alter their abilities through challenge, hard work, perserverance, and the mental attitude that growth is attainable. Each person has some growth and some fixed mindset beliefs. Its important to understand that the fixed mindset is normally adopted because it benefits the person. As Dweck laments: “It told them who they were or who they wanted to be (a smart, talented child) and it told them how to be that (perform well). In this way it provided a formula for self-esteem and path to love and respect from others.” Often people can fall into the trap of results, whereby succeeding in something makes me good at it and failing makes me bad vs. praising and focusing on effort and improvement. For people that become hyperfocused on results, effort can be viewed as lowly. “If you are considered a genius, a talent, or a natural - then you have a lot to lose. Effort can reduce you. The idea of trying and still failing - of leaving yourself without any excuses - is the worst fear within the fixed mindset.” As someone who has put in significant effort into things like sports, only to lose in critical games, this sentence really resonated with me. Often you believe the effort should be rewarded with results, that is the dream described by coaches. But sometimes its not, and you have to wonder whether the effort is really worth it. However, this is a fixed mindset approach. The effort you put in is what establishes the long-term habit of success. Failures can occur from randomness. Failures could also signal that a change in approach is necessary, and often highlights an issue that had been papered over for one reason or another. The effort and the grind and the process are the fun part.

Managing and Teaching. One of the craziest things about mindsets is how easily they can be primed. Several studies discussed in the book place participants into a growth or fixed mindset with simple prompts. “Joseph Martocchio conducted a study of employees who were taking a short computing training course. Half of the employees were put into a fixed mindset. He told them it was all a matter of how much ability they possessed. The other half were put in a growth mindset. He told them that computer skills could be developed through practice. Those in the growth mindset gained considerable confidence in their computer skills as they learned, despite the many mistakes they inevitably made. But because of those mistakes, those with the fixed mindset actually lost confidence in their computer skills as they learned!” All day, every day, we are slipping in and out of different mindsets, often at the prompting of others. And frequently, these mindsets are little conversations going on in the back of our heads! Its important to try to recognize when you are slipping into a fixed mindset, and reframe the thought as a growth mindset one! Changing one’s perception of their own abilities is difficult, but that didn’t stop Marva Collins. “Collins took inner-city Chicago kids who had failed in the public schools and treated them like geniuses. Many of them had been labled ‘learning disabled’ or ‘emotionally disturbed.’..By June, they reached the middle of the fifth grade reader, studying Aristotle, Aesop, Tolstoy, Shakespeare along the way.” Collins set a strong upfront contract with her students: “None of you has ever failed. School may have failed yhou. Well, goodbye to failure, children. Welcome to success. You will read hard books in here and understand what you read. You will write every day…But you must help me to help you. If you don’t give anyhting, don’t expect anything. Success is not coming to you, you must come to it.” Collins raised the kids’ standard, while maintaining a compassionate and nurturing environment. This combination of challenge and nurture can produce wonderful growth. Its important that people don’t feel judged, but rather like someone is pushing them and trying to help them improve.

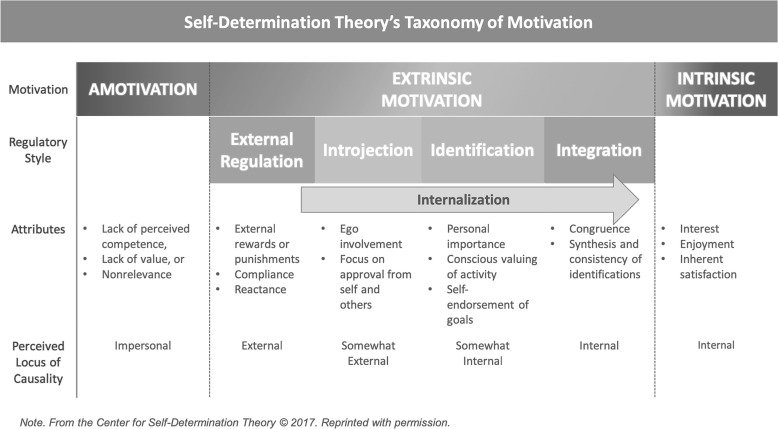

Motivation, Talent, and Mindset. Many people believe in naturals, indiviudals that simply rolled out of bed and became unbelievable athletes, leaders, business people, etc. They often miss the painstaking process of growth that led up to their eventual success. People often correlate talent with prior successes, forgetting the ways in which systems can produce mediocre talent from renowned systems. And frequently, society, parents, friends, and companions praise eachother for talent or success, rather than effort. In his book Malcolm Gladwell discusses the role that talent plays in an individual’s mindset. “Gladwell concludes that when people live in an environment that esteems them for their innate talent, they have grave difficult when their image is threatened. ‘They will not take the remedial course. They will not stand up to investors and the public and admit that they were wrong. They’d sooner lie.’” When we understand the basis of motivation, we can see why people feel threatened when they hold a fixed mindset about their “innate talent.” Self-determination theory speculates that motivation exists on a spectrum from amotivation (or complete lack of motivation) to extrinsic to intrinsic. There are several types of extrinsic motivation as you move along the spectrum to more internalized motivation: External regulation is motivation based on external rewards like compliance or money; Introjected motivation is based on approval from others and social acceptance; Identified motivation is based on consciously valuing the activity; and Integrated motivation is based on self-congruence, or I do this activity because this is the person I am. Lastly, we have full intrinsic motivation, where we pursue things solely because we enjoy doing that activity. For many high performing individuals, their passions seem to fluctuate between extrinsic motivators and intrinsic motivators. The reason we may feel threatened when we have a fixed mindset and our talent comes into question could stem from maintaining an identified or integrated motivation with an activity. For example, if you believe yourself to be a shrewd business person, and the motivation you feel to execute a business strategy comes from that belief that you are excellent, when you make a terrible decision you are faced with a view that sits in direct contrast to how you viewed yourself. This cognitive dissonance can cause severe depression. A growth mindset may reframe the terrible decision as a learning opportunity. Furthermore, a growth mindset may mean laughing at the decision, and getting excited about the challenge caused by it, placing more of the motivation on just executing the business strategy vs. the results of the strategy.

Business Themes

Lou Gerstner and IBM turnaround. IBM is currently facing challenges. Despite spinning off its services unit Kyndryl in November 2021, IBM’s stock remains at a negative return since June 2018. This isn’t the first time IBM’s business has gone off the rails. The 1970s and early 80s were so prosperous for IBM that their culture had gone sideways. A pervasive sense of entitlement filled the air. A 1990 Washington Post article discussed their challenges: “Since 1986, IBM has cut its work force three times. Its no-layoff policy (honored even in the Depression) seems vulnerable. So far all reductions have occurred through voluntary retirements. IBM has lagged in some new computer markets; workstations (souped-up personal computers) are an example. Profits have faltered. In 1988 they were nearly $800 million less than in 1984, despite a $13 billion rise in revenues. IBM's stock is trading around 100, down from the 1987 peak of 175 .” The company even came under antitrust investigation for monopolistic behavior (cough, sound familiar?). When all was lost, the board of directors turned to Lou Gerstner, who had successfully run the Travel Services division of American Express and led RJR Nabisco after KKR’s massive $25B buyout in 1989. Gerstner opened the channels of communication, disbanded the management committee, and tried to dismantle IBM’s hierarchical culture. He shifted bonus measures to broader measures like IBM’s overall performance, instead of narrow measures like a division’s EBITDA. The bonus structure change fostered teamwork across the company. By the time Gerstner stepped down in 2002, its market cap had risen from $29B to $168B. However, what’s excluded from the story is Gerstner’s tactics, he laid off 60,000 workers, including 35,000 in 1994. Gerstner was also handsomely rewarded for this turnaround, netting hundreds of millions in stock through option plans. Laying off workers and making money aren’t inherently bad, and Gerstner’s leadership is still commendable - but its important to note that it likely wasn’t just a mindset shift that led to his success at IBM.

Jack Welch - the Best or the Worst. Jack Welch is another executive lauded throughout the book. Long praised for his aggressive management style and focus on performance, Welch was considered an unquestionable genius when he was CEO of GE. Welch became CEO of GE in 1981 and embarked on a 20 year run filled with cost-cutting, layoffs, and countless acquisitions. Under Welch, GE made 600 acquisitions and pushed the company into every aspect of business, including owning TV station NBC and investment bank Kidder Peabody at one point. Kidder Peabody went through two famous trading scandals. In 1987, it was involved in Ivan Boesky’s insider trading scheme, and several years later (under GE’s ownership) it was the subject of another, more egregious trading scandal, whereby a trader placed fake trades and was paid bonuses based on fake results. Dweck uses this as a way to show Welch’s growth mindset: “There is a whole chapter titled ‘Too Full of Myself’ about the time he was on an acquisition roll and felt he could do no wrong. ‘The Kidder experience never left me’ It taught him that ‘there’s only a razor’s edge between self-confidence and hubris. This time hubris won and taught me a lesson I would never forget.” GE’s market value increased from $12B in 1981 to $410B in 2001. In 1999, Fortune named him manager of the century. He launched GE Capital, which would peak around 40% of its business: “But blue-chip G.E. had none of those burdens, which meant that, when it came to making money, Welch’s non-bank bank could put real banks to shame. He then used the proceeds from G.E. Capital to acquire hundreds of companies. In the warm glow of G.E.’s riches, Welch articulated a series of principles that captivated his peers. Fire nonperformers without regret. Shed any business that isn’t first or second in its market category. Your duty is always to enrich your shareholders.” But let’s dig into the not so bright side of Jack Welch. When he became CEO, Welch laid off hundreds of thousands of employees, taking GE’s total from 411,000 in 1980 to 299,000 at the end of 1985. He championed an Enron like approach of ranking employees and firing the bottom 10% every year. He was married three times, and had an extra-marital affair with a Harvard Business Review reporter, who eventually became his third wife. After Welch left GE, its stock fell precipitously, as it tried to unwind GE Capital and all of the other 600 acquisitions it had made during the conglomerate era of the 1980s. Welch’s retirement package was absolutely egregious: “After Welch left G.E., the details of his retirement package were made public. It included a pension of $7.4 million a year and a mountain of perks. He got the use of a company Boeing 737, at an estimated cost of $3.5 million a year. He got an apartment in Donald Trump’s 1 Central Park West, plus deals at the restaurant Jean-Georges downstairs, courtside seats at Knicks games, a subsidy for a car and driver, box seats at the Metropolitan Opera, discounts on diamond and jewelry settings, and on and on—all this for someone worth an estimated nine hundred million dollars. And then, finally, G.E. agreed to pay the monthly dues at the four golf clubs where he played.” If we can learn anything from Jack Welch about growth mindset, its that you can be both a fixed mindset person and a growth mindset person, judging and communicating.

Sports Mindset. Sports provide an excellent training ground to explore mindset. According to Dweck, growth mindset athletes tend to find success in doing their best, in learning and improving. They also find setbacks motivating and informative, digesting them as a wake-up call. Lastly, growth mindset athletes take more control of their process. Here Dweck discusses Tiger Wood’s Dad’s approach to toughening his son: “Tiger’s dad made sure to teach him how to manage his attention and his course strategy. Mr. Woods would make loud noises or throw things just as little Tiger was about to swing.” Woods would often envision a younger rival, pouring himself into learning shots” I have to give myself a reason to work so hard. He’s out there somewhere. He’s twelve.” While this psychological manipulation produced an amazing golfer, it also caused a lot of trauma. Tiger’s complicated relationship with his father and subsequent extra-marital affairs and DUIs have somewhat overshadowed his amazing golf achievements. Another reputationally poor example in the book is Lenny Dykstra. Dykstra, a man who has been charged with well over 25 misdemeanor and felony accounts and who personally filed for bankruptcy, is said to have had a growth mindset by Billy Beane, who claimed, “He had no concept of failure…And I was the opposite.” Beane eventually became GM of the Oakland Athletics, and focused their scouting and recruiting efforts on statistically sound and collegial players, rather than popular stars. Dykstra’s lack of failure concept was recently echoed by soccer star Kevin De Bruyne. “A lot of times when people make mistakes, they don't do it anymore. When I make a mistake, I try to do it twice more and if I make it twice more I'll do it again. I think in in one kind of way [its] learning where you go wrong and I think you understand more out of it if you make errors.” Kevin clearly displays a growth mindset and love for soccer.

Dig Deeper