This month we dive into the fintech space for the first time! Glenbrook Partners is a famous payments consulting company. This classic book describes the history and current state of the many financial systems we use every day. While the book is a bit dated and reads like a textbook, it throws in some great real-world observations and provides a great foundation for any payments novice!

Tech Themes

Mapping Open-Loop and Closed-Loop Networks. The major credit and debit card providers (Visa, Mastercard, American Express, China UnionPay, and Discover) all compete for the same spots in customer wallets but have unique and differing backgrounds and mechanics. The first credit card on the scene was the BankAmericard in the late 1950’s. As it took off, Bank of America started licensing the technology all across the US and created National BankAmericard Inc. (NBI) to facilitate its card program. NBI merged with its international counterpart (IBANCO) to form Visa in the mid-1970’s. Another group of California banks had created the Interbank Card Association (ICA) to compete with Visa and in 1979 renamed itself Mastercard. Both organizations remained owned by the banks until their IPO’s in 2006 (Mastercard) and 2008 (Visa). Both of these companies are known as open-loop networks, that is they work with any bank and require banks to sign up customers and merchants. As the bank points out, “This structure allows the two end parties to transact with each other without having direct relationships with each other’s banks.” This convenient feature of open-loop payments systems means that they can scale incredibly quickly. Any time a bank signs up a new customer or merchant, they immediately have access to the network of all other banks on the Mastercard / Visa network. In contrast to open-loop systems, American Express and Discover operate largely closed-loop systems, where they enroll each merchant and customer individually. Because of this onerous task of finding and signing up every single consumer/merchant, Amex and Discover cannot scale to nearly the size of Visa/Mastercard. However, there is no bank intermediation and the networks get total access to all transaction data, making them a go-to solution for things like loyalty programs, where a merchant may want to leverage data to target specific brand benefits at a customer. Open-loop systems like Apple Pay (its tied to your bank account) and closed-loop systems like Starbuck’s purchasing app (funds are pre-loaded and can only be redeemed at Starbucks) can be found everywhere. Even Snowflake, the data warehouse provider and subject of last month’s TBOTM is a closed-loop payments network. Customers buy Snowflake credits up-front, which can only be used to redeem Snowflake compute services. In contrast, AWS and other cloud’s are beginning to offer more open-loop style networks, where AWS credits can be redeemed against non-AWS software. Side note - these credit systems and odd-pricing structures deliberately mislead customers and obfuscate actual costs, allowing the cloud companies to better control gross margins and revenue growth. It’s fascinating to view the world through this open-loop / closed-loop dynamic.

New Kids on the Block - What are Stripe, Adyen, and Marqeta? Stripe recently raised at a minuscule valuation of $95B, making it the highest valued private startup (ever?!). Marqeta, its API/card-issuing counterpart, is prepping a 2021 IPO that may value it at $10B. Adyen, a Dutch public company is worth close to $60B (Visa is worth $440B for comparison). Stripe and Marqeta are API-based payment service providers, which allow businesses to easily accept online payments and issue debit and credit cards for a variety of use cases. Adyen is a merchant account provider, which means it actually maintains the merchant account used to run a company’s business - this often comes with enormous scale benefits and reduced costs, which is why large customers like Nike have opted for Adyen. This merchant account clearing process can take quite a while which is why Stripe is focused on SMB’s - a business can sign up as a Stripe customer and almost immediately begin accepting online payments on the internet. Stripe and Marqeta’s API’s allow a seamless integration into payment checkout flows. On top of this basic but highly now simplified use case, Stripe and Marqeta (and Adyen) allow companies to issue debit and credit cards for all sorts of use cases. This is creating an absolute BOOM in fintech, as companies seek to try new and innovative ways of issuing credit/debit cards - such as expense management, banking-as-a-service, and buy-now-pay-later. Why is this now such a big thing when Stripe, Adyen, and Marqeta were all created before 2011? In 2016, Visa launched its first developer API’s which allowed companies like Stripe, Adyen, and Marqeta to become licensed Visa card issuers - now any merchant could issue their own branded Visa card. That is why Andreessen Horowitz’s fintech partner Angela Strange proclaimed: “Every company will be a fintech company.” (this is also clearly some VC marketing)! Mastercard followed suit in 2019, launching its open API called the Mastercard Innovation Engine. The big networks decided to support innovation - Visa is an investor in Stripe and Marqeta, AmEx is an investor in Stripe, and Mastercard is an investor in Marqeta. Surprisingly, no network providers are investors in Adyen. Fintech innovation has always seen that the upstarts re-write the incumbents (Visa and Mastercard are bigger than the banks with much better business models) - will the same happen here?

Building a High Availability System. Do Mastercard and Visa have the highest availability needs of any system? Obviously, people are angry when Slack or Google Cloud goes down, but think about how many people are affected when Visa or Mastercard goes down? In 2018, a UK hardware failure prompted a five-hour outage at Visa: “Disgruntled customers at supermarkets, petrol stations and abroad vented their frustrations on social media when there was little information from the financial services firm. Bank transactions were also hit.” High availability is a measure of system uptime: “Availability is often expressed as a percentage indicating how much uptime is expected from a particular system or component in a given period of time, where a value of 100% would indicate that the system never fails. For instance, a system that guarantees 99% of availability in a period of one year can have up to 3.65 days of downtime (1%).” According to Statista, Visa handles ~185B transactions per year (a cool 6,000 per second), while UnionPay comes in second with 131B and Mastercard in third with 108B. For the last twelve months end June 30, 2020, Visa processed $8.7T in payments volume which means that the average transaction was ~$47. At 6,000 transactions per second, Visa loses $282,000 in payment volume every second it’s down. Mastercard and Visa have always been historically very cagey about disclosing data center operations (the only article I could find is from 2013) though they control their own operations much like other technology giants. “One of the keys to the [Visa] network's performance, Quinlan says, is capacity. And Visa has lots of it. Its two data centers--which are mirror images of each other and can operate interchangeably--are configured to process as many as 30,000 simultaneous transactions, or nearly three times as much as they've ever been asked to handle. Inside the pods, 376 servers, 277 switches, 85 routers, and 42 firewalls--all connected by 3,000 miles of cable--hum around the clock, enabling transactions around the globe in near real-time and keeping Visa's business running.” The data infrastructure challenges that payments systems are subjected to are massive and yet they all seem to perform very well. I’d love to learn more about how they do it!

Business Themes

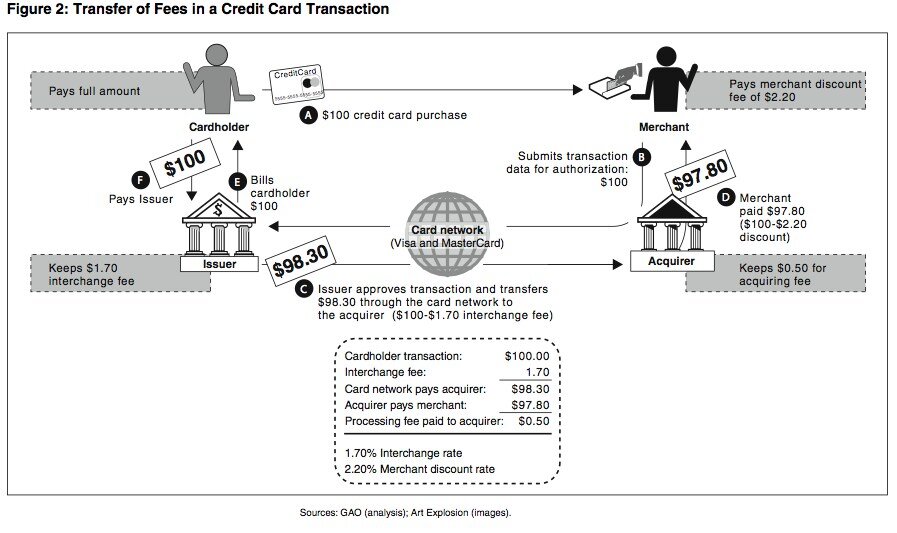

What is interchange and why does it exist? BigCommerce has a great simple definition for interchange: “Interchange fees are transaction fees that the merchant's bank account must pay whenever a customer uses a credit/debit card to make a purchase from their store. The fees are paid to the card-issuing bank to cover handling costs, fraud and bad debt costs and the risk involved in approving the payment.” What is crazy about interchange is that it is not the banks, but the networks (Mastercard, Visa, China UnionPay) that set interchange rates. On top of that, the networks set the rates but receive no revenue from interchange itself. As the book points out: “Since the card netork’s issuing customers are the recipients of interchange fees, the level of interchange that a network sets is an important element in the network’s competitive position. A higher level of interchange on one network’s card products naturally makes that network’s card products more attractive to card issuers.” The incentives here are wild - the card issuers (banks) want higher interchange because they receive the interchange from the merchant’s bank in a transaction, the card networks want more card issuing customers and offering higher interchange rates better positions them in competitive battles. The merchant is left worse off by higher interchange rates, as the merchant bank almost always passes this fee on to the merchant itself ($100 received via credit card turns out to only be $97 when it gets to their bank account because of fees). Visa and Mastercard have different interchange rates for every type of transaction and acceptance method - making it a complicated nightmare to actually understand their fees. The networks and their issuers may claim that increased interchange fees allow banks to invest more in fraud protection, risk management, and handling costs, but there is no way to verify this claim. This has caused a crazy war between merchants, the card networks, and the card issuers.

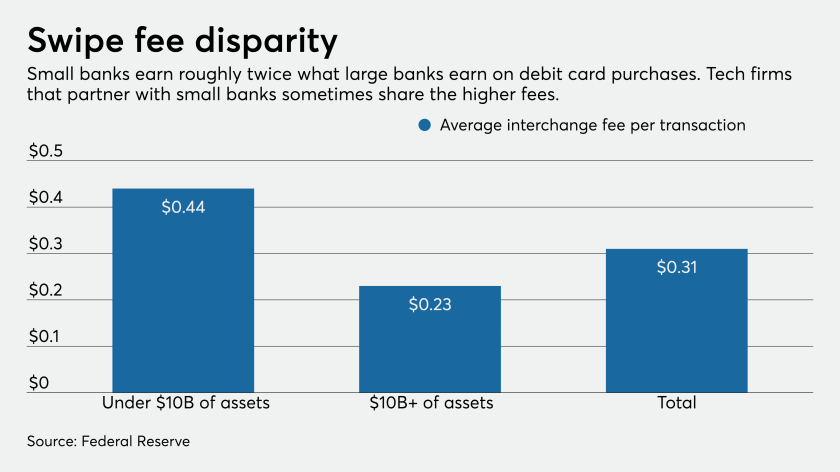

Why is Jamie Dimon so pissed about fintechs? In a recent interview, Jamie Dimon, CEO of JP Morgan Chase, recently called fintechs “examples of unfair competition.” Dimon is angry about the famous (or infamous) Durbin Amendment, which was a last-minute addition included in the landmark Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010. The Durbin amendment attempted to cap the interchange amount that could be charged by banks and tier the interchange rates based on the assets of the bank. In theory, capping the rates would mean that merchants paid less in fees, and the merchant would pass these lower fees onto the consumer by giving them lower prices thus spurring demand. The tiering would mean banks with >$10B in assets under management would make less in interchange fees, leveling the playing field for smaller banks and credit unions. “The regulated [bank with >$10B in assets] debit fee is 0.05% + $0.21, while the unregulated is 1.60% + $0.05. Before the Durbin Amendment the fee was 1.190% + $0.10.” While this did lower debit card interchange, a few unintended consequences resulted: 1. Regulators expected that banks would make substantially less revenue, however, they failed to recognize that banks might increase other fees to offset this lost revenue stream: “Banks have cut back on offering rewards for their debit cards. Banks have also started charging more for their checking accounts or they require a larger monthly balance.” In addition, many smaller banks couldn’t recoup the lost revenue amount, leading to many bankruptcies and consolidation. 2. Because a flat rate fee was introduced regardless of transaction size, smaller merchants were charged more in interchange than the prior system (which was pro-rated based on $ amount). “One problem with the Durbin Amendment is that it didn’t take small transactions into account,” said Ellen Cunningham, processing expert at CardFellow.com. “On a small transaction, 22 cents is a bigger bite than on a larger transaction. Convenience stores, coffee shops and others with smaller sales benefited from the original system, with a lower per-transaction fee even if it came with a higher percentage.” These small retailers ended up raising prices in some instances to combat these additional fees - causing the law to have the opposite effect of lowering costs to consumers. Dimon is angry that this law has allowed fintech companies to start charging higher prices for debit card transactions. As shown above, smaller banks earn a substantial amount more in interchange fees. These smaller banks are moving quickly to partner with fintechs, which now power hundreds of millions of dollars in account balances and Dimon believes they are not spending enough attention on anti-money laundering and fraud practices. In addition, fintech’s are making money in suspect ways - Chime makes 21% of its revenue through high out-of-network ATM fees, and cash advance companies like Dave, Branch, and Earnin’ are offering what amount to pay-day loans to customers.

Mastercard and Visa: A history of regulation. Visa and Mastercard have been the subject of many regulatory battles over the years. The US Justice Department announced in March that it would be investigating Visa over online debit-card practices. In 1996, Visa and Mastercard were sued by merchants and settled for $3B. In 1998, the Department of Justice won a case against Visa and Mastercard for not allowing issuing banks to work with other card networks like AmEx and Discover. In 2009, Mastercard and Visa were sued by the European Union and forced to reduce debit card swipe fees by 0.2%. In 2012, Mastercard and Visa were sued for price-fixing fees and were forced to pay $6.25B in a settlement. The networks have been sued by the US, Europe, Australia, New Zealand, ATM Operators, Intuit, Starbucks, Amazon, Walmart, and many more. Each time they have been forced to modify fees and practices to ensure competition. However, this has also re-inforced their dominance as the biggest payment networks which is why no competitors have been established since the creation of the networks in the 1970’s. Also, leave it to the banks to establish a revenue source that is so good that it is almost entirely undefeatable by legislation. When, if ever, will Visa and Mastercard not be dominant payments companies?